Dairy | Milk

What’s in a name? The fight over milk

The argument over what can legally be sold using the name milk has been going back and forth for some years now. While European courts have been active on the subject, the US is yet to update federal legislature in response to the rise of dairy-alternatives. Peter Nilson takes a look at the current state of affairs across the pond.

The dairy industry has long taken issue with dairy-free alternatives using traditional gastronomic terms. In 2014, Swedish oat drink company Oatly was taken to court by the Swedish Dairy Association, due to its advertising campaign featuring the slogan ‘It’s like milk, but made for humans’. The courts ruled in favour of the Swedish Dairy Association.

A 2017 European Court of Justice ruling reserved the terms ‘milk’, ‘cheese’ and ‘yoghurt’ for products made with animal milk in the European Union. However, it’s not a simple regulation, as a clause in the ruling allows non-dairy producers to continue with ‘traditionally used’ terms.

In practice, this means there are roughly 130 exceptions to the ruling across different languages. For example, the terms coconut milk, peanut butter and almond milk are all allowed.

Throughout the US, dairy producers have also been lobbying for protection of these terms at both state and federal levels since 1997; however wide-reaching legislation has not yet been decided.

What’s the FDA’s current stance on the matter?

“An almond doesn’t lactate, I will confess,” Scott Gottlieb, the former commissioner of the FDA, said back in 2018 – referencing the FDA’s current definition of milk as a liquid derived from a lactating cow.

It should be noted that the dairy industry doesn’t seem to have any objections to other mammal-derived milk – such as sheep's milk – using the term milk, even though the FDA’s definition explicitly states ‘one or more healthy cows’.

The FDA re-opened the comment period on a proposal to amend definitions of milk in its standards of identity at the end of 2019. But the proposal was first issued in 2005 – that’s quite the wait for a conclusion on the matter.

Gottlieb left the FDA last year, and the lack of movement on the issue by the agency prompted 58 members of the House of Representatives to write to the current commissioner, Stephen Hahn, back in February.

In the letter, the lawmakers urged the agency to finish the review of the definition of milk products that began under Gottlieb’s tenure.

Hahn clearly echoes the same sentiment – having stated prior to his confirmation as FDA commissioner that the American people "need this so that they can make the appropriate decisions for their health and for their nutrition”.

Do consumers really need legislation to help their decisions?

It’s perfectly understandable that the dairy industry has a huge interest in regulating the labelling of milk products. But the argument that dairy-free products using the same name as dairy products causes confusion amongst consumers does seem more than a little condescending at first glance.

Indeed, those opposing the dairy industry’s efforts have repeatedly slammed the argument for ‘insulting consumer intelligence’.

However, the argument that dairy producers have been making recently is a bit more nuanced. American dairy lobby group the National Milk Producers Federation (NMPF) assert that the doubt isn’t centred on the source of these products.

Instead, it says this is an argument about the inherent assumption consumers might have about the nutritional value of a product named ‘milk’.

What we're really fighting on here is a public health issue.

“What we're really fighting on here is a public health issue,” says the NMPF’s senior vice president of communications, Alan Bjerga. “We're taking a look at confusion, which is amply documented by research, that consumers have about the nutritional content of these beverages.

“When you call something a milk, you're cueing to a consumer that this is probably the same [nutritionally] as a dairy beverage, it's just made of something else.”

As opposed to a debate on consumer intelligence, this train of thought is a little more concerning – those consumers who aren’t au-fait with plant-based alternatives may very well make this assumption.

For example, per cup, milk from cows contains 110 calories, whereas plant-based alternatives can range from 30-150 calories depending on the plant source. There are 2.5g of fat in a cup of cow's milk, but the amount in plant-based is anywhere from 0g (almond) to 11g (peanut).

Across the board in fact, depending on which plant is used, the nutritional content of plant-based milk does vary dramatically compared to cow’s milk.

Surely everyone can figure this out by themselves?

On the other side of the debate, the Plant Based Foods Association (PBFA) has surmised in a statement made to the FDA that consumers are fully aware of what they are purchasing.

The terms milk, cheese and butter “represent functionality, form and taste, not necessarily the origin of the primary ingredient.” The PBFA also made it clear that dairy-free products already use clear qualifiers on their labels such as non-dairy, plant-based and/or vegan.

And a preliminary analysis of the comments posted so far to the FDA, conducted by the PBFA, found that at least 74% of people are in support of using the term ‘milk’ on the labels of plant-based milk products.

A reasonable consumer wouldn’t assume that two distinct products have the same nutritional content.

The courts have also, in some cases, taken the PBFA’s side. Back in 2018, The US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled that the term ‘almond milk’ is 'not deceptive', concluding that: “a reasonable consumer wouldn’t assume that two distinct products have the same nutritional content”.

But it’s not just the nutritional or conceptual arguments that the PBFA is opposed to, with economic matters just as important.

According to UK research firm Mintel, plant-based sales are on the rise, with a 30% increase in the UK since 2015 and over 60% in the US since 2012. The Good Food Institute published a study in 2019 stating the US market for Plant-Based milk is now worth $1.9bn.

If the FDA rules that the plant-based sector can’t use terms like milk, it could cause huge setbacks to a growing industry. “The marketplace disruption being pushed by the dairy lobby would hinder innovation, create untenable costs for our members, and ultimately be found unconstitutional, making the entire effort a waste of everybody’s time and resources,” said Michele Simon, executive director of PBFA.

“We encourage the FDA to abide by free-market principles and not restrict labelling to unfairly favour the dairy industry,” Simon adds.

It’s a perfect response that the FDA won’t be able to ignore – the terms ‘unconstitutional’ and ‘free market’ will catch the attention of many in US legislature.

How will the FDA’s actions affect the future of milk?

The FDA may very well make a decision that will irk the dairy industry, by concluding that the term milk is being used so ubiquitously with plant-based products that the definition should be adjusted to include them. Or, it could instead introduce a secondary definition for ‘plant-based milk’ or similar.

However, Hahn’s apparent leaning to the NMPF’s side of the argument could sway the FDA into enforcing its current definition of milk, which would lead to plant-based products having to remove the term from their branding and marketing.

So if the Dairy industry succeeds and plant-based products are forced to rescind the title of milk, what will that mean for dairy-free brands? Some creative inspiration might be found in Sweden, where dairy conglomerate Arla has continued the so-called ‘Milk War’ with plant-based companies such as Oatly.

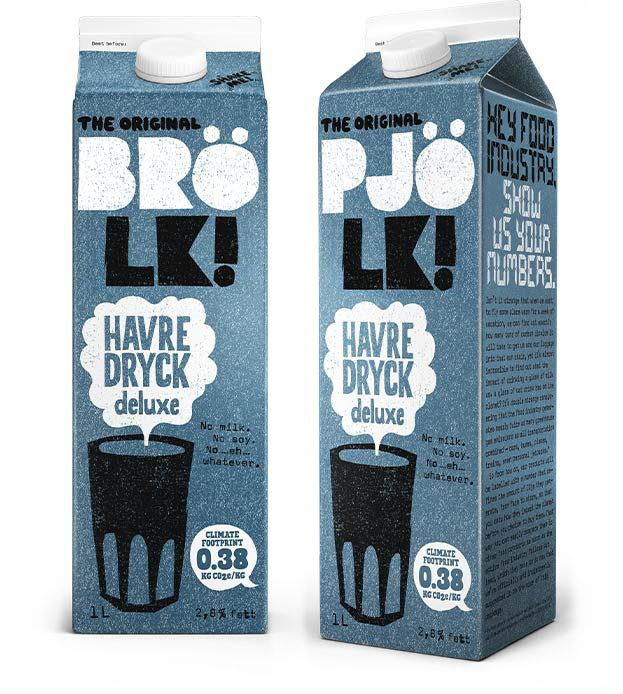

Oatly’s packaging with the names brölk and pjölk. Image: Oatly.

In a TV ad that pokes fun at Oatly et al, Arla calls dairy-free milk products variations on the Swedish word for milk (mjölk), such as brölk, pjölk and trölk.

Unfortunately though, Arla missed a step in the campaign and neglected to trademark these faux-milk terms. Oatly subsequently registered the words as trademarks and proceeded to use them in its own marketing activities, even printing them on cartons.

It’s the kind of marketing we’ve come to expect from many plant-based companies over the years, so who knows, maybe the US dairy aisles will one day be full of milk made using cows, and molk made using plants.

But consumers will probably be able to figure out the difference no matter what the name is.